The captain and the philosopher

Sartre, Kahneman, and how goal-setting can limit our lives

Only the guy who isn’t rowing has time to rock the boat. — Jean-Paul Sartre

In his book The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman describes how the various interfaces we interact with throughout our daily lives can sometimes serve to imperceptibly increase our levels of anxiety. The elevator button that didn’t work as expected. The door with no indication as to whether it should be pulled or pushed. We finish our days stressed out, without fully knowing why. As we find ourselves increasingly buried in new technologies, these factors influence us now more than ever. Much like the boiling frog, we tend not to notice the little things that affect us, but these little things add up. Thankfully, principles of good user interface design are receiving increasing attention.

Under the motivation that learning about such things makes us less susceptible to them, I think I’ve put my finger on another common source of anxiety that our modern culture can put us at risk of unless we are careful — the anxiety that comes from not taking responsibility for our decisions.

Let me expand on this. The story will involve the school system, naval vessels, and a famous French existentialist philosopher. Do bear with me.

The school system

When we are at school, we are taught the value of sacrifice. If you give up your time, sit quietly in a classroom and suppress your natural spontaneity for 12 or 13 years or so, they say, good things will happen as a result. In the likely event of there not being a pot of gold waiting as a reward for all that, however, comes the inevitable realisation that more work is likely to be required to achieve any tangible results, and that news may come as a disappointment to the newly graduated student.

The first step in maturing, or deprogramming from the school system having left it, is the setting of one’s own goals. Nobody tells you what to learn anymore. The onus is on the individual to introspect, discover their own values and thus set some future goals of their own creation. Introspection is important at this stage because goals imply values and values imply goals.

This is an exciting and empowering time. This is the consolation that the future is more under your control and that you can pursue your passions and ‘follow your bliss’ as opposed to a structured curriculum. But the bug has already bitten. That bug is the notion that there is some state in the future where life really starts to get going.

Even if your goals are self-directed, there is still the inculcated notion that to get to where you want to be, you need to sacrifice the current moment. Life is a zero-sum game, you have come to think. You give up something now for something good later, thats the deal, and if you are smart about it, that good thing will be really good.

Naval vessels

Let’s pause for a moment, and allow me to make a brief digression into psychology, and what happens when we set goals.

A good analogy for the brain and its functions (or at least, good enough for our current purposes) is that of a giant ship, and perched atop that ship is the captain:

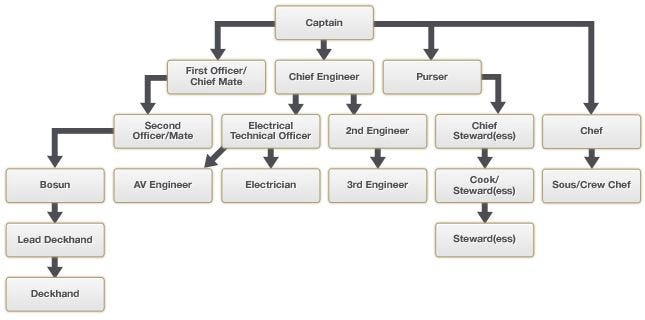

Beneath him are his crew. There is a chain of command such that decisions of higher importance are made by the more senior staff. At the lowest level, simple, easy decisions are made that take into account the outside world, but with no-one to serve as ‘advisors’. Sometimes, their actions may influence the course of the ship, but such actions are so mechanistic that they needn’t be delegated to any senior members of staff.

Sometimes the decisions to be made are rather more complicated, and the officers on the deck need to be consulted as to what to do. Perhaps one of the lowly deckhands has spotted an iceberg approaching. Instead of acting immediately, he passes this information on to one of his seniors, who in turn decides it is too important for him to handle, and so on, until it reaches the seniority of the captain. He can decide, based on the aggregate of information from his advisors, whether it is necessary to steer the ship or to continue on its current course.

The captain in our case, represents the higher executive functions of the brain. You might call this the ego, you might call this ‘System 2' (people have been dichotomising the brain for a while). The deckhands are the low level sensory receptors and their actions that they take of their own volition are considered ‘reflexes’. Burn your hand on a hot iron, the hands snaps back before ‘you’, the captain, ever realise. That sort of thing.

What is considered ‘willpower’ is the captain exerting his senior authority. He can steer the ship in a certain direction and trust that his crew will be on his side working to fulfil that objective. Have you ever been mulling over a problem, only for the solution to come to you whilst you were brushing your teeth? That’s thanks to the crew labouring through the night to fulfil the objectives set by the captain, and eagerly presenting their findings in the morning.

The captain isn’t always consulted about things though. In fact, he is often left with very little to do. The book Thinking Fast & Slow explains that it is relatively expensive (in terms of energy and effort) to employ your executive functions, such that the rest of the brain (System 1) has evolved to be very good, and very quick, at handling things all on its own.

When you drive to work, or when you swipe your card on the metro, such actions are so common and so automatic that it frees up enough mental resources to daydream about anything you want while doing it. This is akin to the captain sitting atop his station, reading the newspaper, or watching TV while the remainder of its crew is busily engaged in the running of the ship.

Think about your life. Is the captain usually active in steering the ship, or is he slacking on the job? Thinking Fast & Slow is not intended to be a self-help book, but I remember studying it and thinking ‘gosh, I think my System 2 might be broken’. The truth was that my System 2 was mainly employed in daydreaming, whilst most of my activities were habitual enough to be delegated to fast, automatic, and reflexive processing. Even when talking, I wasn’t thinking all that much about what I was talking about.

What happens if the captain is so lazy, if he so often fails to take the initiative of travelling into uncharted waters, and just lets his industrious crew do all the work? What if he just sets the bearings for the next 6 months and sits on his butt that whole time? What if something unforeseen happens, should he just trust that his crew know what they are doing?

It’s his ship! Isn’t he responsible for it?

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre was a French philosopher, and his magnum opus was Being And Nothingness, a dense, highly technical book that I cannot claim to have read all or even most of. However, there is a particularly famous section that I have read, titled Bad Faith, in which he describes the various affectations of a waiter he sees in a cafe. If you haven’t read that part yourself, check it out. The waiter, as described and interpreted by Sartre, is merely ‘playing at’ being a waiter rather than exhibiting the behaviour that one might expect of a spontaneous, sincere human being. He is ultimately lying to himself — the waiter is well aware of his self-imposed chains, but nevertheless he chooses to limit himself in this formulaic way.

I know what this feels like. I’ve had jobs where I have felt required to give up my spirit as well as my time. My reluctance to do this often made me not a very good employee and probably made me look all the more insincere. Luckily I never worked at a grocery store, because one sentence therefore really stood out for me:

A grocer who dreams is an insult to the buyer

But a less-cited example of Bad Faith that Sarte gives that I find most fascinating, is one he gives a little earlier in the book — that of a woman on a date. During conversation, Sartre describes, the man takes her hand, and suddenly a decision imposes itself upon her. Should she acknowledge the action and assent to it, thereby escalating the romance? Or should she withdraw her hand and produce the opposite effect? In fact, she does neither:

…the young woman leaves her hand there, but she does not notice that she is leaving it. She does not notice because it happens by chance that she is at this moment all intellect… the divorce of the body from the soul is accomplished; the hand rests inert between the warm hands of her companion — neither consenting nor resisting — a thing

That’s interesting. The body has split off from the ‘intellect’, the body divorced from the soul, all for the purposes of avoiding a decision.

Putting it all together

When I first read that passage on Bad Faith, I realised how profound it was, and began to notice such moments of splitting of body and soul regularly in my life.

Just the other day I was on my way to get a coffee. I had set a goal for myself, and that goal was caffeine. The sun was shining, but I didn’t particularly care to notice. My goal was laid out, and my strategy clear. It was not a leisurely stroll, it was a purposeful one. I could have enjoyed the sun, but no, I was just after coffee.

Unexpectedly, a woman, a tourist, raised her camera and pointed it across the path I was about to walk and aiming at a couple posing for the photo on the other side. A decision imposed itself: do I walk straight through her camera’s field of vision? Or should I wait and let her take the photo?

As an English person, I tend to shudder at the possibility of being rude, so I could have stopped, smiled and politely waited. Alternatively, I could have unashamedly walked on through. In fact I could make a principle out of it. I live in quite a touristic area, so if I stopped and waited for every photograph to be taken whenever I was about to cut into one, I would hardly get anywhere fast.

In fact, like Sartre’s woman on the date, I did neither. I yielded to the body’s momentum and forged straight ahead; but not unashamedly so. I justified it to myself in the sense that I had a destination and I was merely a passenger in my own body. That if I was being rude it was only my body (as a depersonalised ‘thing’) being rude, because you see, my body has somewhere to be.

To use the analogy of the ship, the captain had set the ships bearings and was at pains to change them now. Perhaps it would be more proper, or even ethical, to change the ships direction, but my captain was a feeble, apologetic one, unwilling to wield his power. Aware of the various options available to him but never one to take them up, he just shrugs with an embarrassed ‘what can you do?’ expression on his face, as if his errant dog had just pooped in the middle of the street and lacked a plastic bag with which to pick it up.

That act, cutting through and possibly including myself in some poor tourist’s holiday photo album, left me with a slight but perceptible negative feeling. It was a quite deliberate act that passed itself off as inadvertence, and so involved an element of self-deception. It was a momentary ‘splitting of body and soul’ of the type that Sartre was talking about. However minor it was, I hadn’t approached the situation 100% sincerely and that small act of never-quite-deciding was enough to affect my mood and composure ever so slightly.

Being excessively goal-directed opens you up to these kinds of ‘bad faith’ experiences all the time. When you set your ship on a long course, it leaves the captain (your ego) with very little to do in the meanwhile, except to ruminate and consider uncharted waters that he will never care to explore. He is not in full control of the ship that his role empowers him to command. Yet this goal-directedness is exactly how we were brought up to be. Our ability to make spontaneous decisions was suppressed from an early age. The captain went to sleep and set his alarm for graduation day.

An ‘authentic’ life has to involve an energetic captain, not a lazy or suppressed one. A captain who make full use of the powers available to him in his role, and does not shirk his responsibilities by delegating them away. He stays receptive to the information made available to him by his crew, and is ready to change course at any moment. The ability to change direction from moment to moment does not have to imply a complete lack of consistency, though. As Emerson says:

The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency.

The ideal scenario is one in which all staff aboard the vessel are always active and aligned in their aims — it is experienced by the individual as relative lack of angst, and perceived by others as assertiveness.

A path forward

Our goals are important and give us a sense of purpose, but they also give us an ‘out’ whenever there is an opportunity for our true selves to manifest, an excuse not to affirm ourselves. These little moments where we see opportunities for self-expression but reject them in favour of some decision made earlier is Bad Faith. These little moments of insincerity can build up throughout our days and our lives, leaving us feeling anxious and lacking control and integrity.

Progress for all of us lies in the ability to commit to a Way that gets us closer to where we want to be but which allows the flexibility to occasionally go off course, and without regret, anxiety or shame, re-awaken the child in you, energise the captain of the ship, and engage in the little moments of life; those that really matter.